The department has signed interagency agreements to outsource six offices to other agencies, including those that manage $28 billion in grants to K-12 schools and $3.1 billion for programs that help students complete college.

There was considerable speculation that a $15 billion program to assist students with disabilities would also be included in the announcement, but that was not the case. Other key functions of the Education Department, including the Office for Civil Rights and federal student aid programs, were also not affected by Tuesday's changes, but a senior department official told reporters that officials are still exploring options for relocating these programs elsewhere in the government.

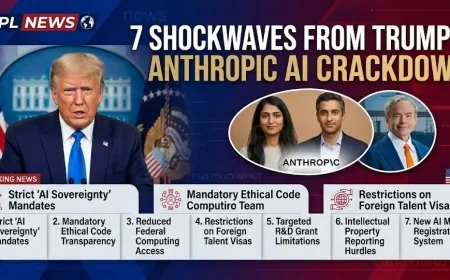

President Donald Trump campaigned on a promise to close the agency, established in 1979, and signed an executive order in March to eliminate it. He asked Education Secretary Linda McMahon to work with Congress to do so, but lawmakers have neither acted nor seriously considered Trump's request.

This is at least partly because any legislation would require Democratic support to pass the Senate, which appears highly unlikely.

McMahon and her supporters advocate for changes to the role of federal education, saying that falling test scores indicate the agency is not delivering the desired results and arguing that Americans are tired of government bureaucracy.

Supporters of the Department of Education say that uniting education programs under one umbrella helps coordinate policies and better serve schools and students. They say the agency helps ensure that priorities important to students, parents, and schools are at the top of the federal agenda. And they argue that the Trump administration's dismantling of the department without congressional approval is illegal.

McMahon has acknowledged that only Congress can abolish the department, but he has vowed to work to eliminate it from within. He has said that the agency's functions could be more easily, and perhaps more effectively, performed elsewhere in the government. This fall, he took the first step by transferring career and technical education programs, including adult education and family literacy initiatives, to the Department of Labor.

"The Trump administration is taking bold steps to dismantle the federal education bureaucracy and return education to the states," McMahon said in a statement on Tuesday. "Cutting through the layers of red tape in Washington is an essential part of our ultimate mission."

Moving offices to other parts of the government won't automatically eliminate red tape or change Washington's influence over states and school districts. States and school boards already control most education decisions, but the Department of Education enforces regulations inherent in federal programs, such as grant funding requirements.

Asked how transferring offices to other departments would return education to states, the senior official said states would have to work with fewer federal agencies. He argued that the purpose of education is to prepare students for the workforce.

He said, "There's no better system than the Department of Labor."

But most K-12 schools no longer typically work with the Department of Labor. The K-12 grant programs the Department of Labor is launching address a range of topics not directly related to the workforce, such as assistance for children living in poverty, after-school programs, and support for rural education. Critics have argued that under this arrangement, states and school districts will have to engage with more federal agencies, not fewer.

David R. Schuler, executive director of the school superintendents association, AASA, said, "It's difficult to understand how shifting core programs out of the department will ensure streamlined operations, especially for the nation's smaller, rural, and under-capacity districts."

Senator Patty Murray (Democrat-Washington) said that federal law requires an act of Congress to close the department. In a statement, she said the administration is pretending that the constitutional separation of powers is "merely a suggestion."

"This is a blatantly illegal attempt to progressively dismantle the Department of Education," Murray said. "And students and their families will suffer, as key programs that help students learn to read or strengthen relationships between schools and families will be handed over to agencies with little or no relevant expertise."

Under the new agreements, the Labor Department will inherit the Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, including 27 K-12 grant programs, and the Office of Postsecondary Education, which administers 14 programs to help students enroll in and complete college. The Education Department will move the Indian education program to the Interior Department; child care access and foreign medical education to the Department of Health and Human Services; and foreign-language education to the State Department.

Some of these are lower-profile offices without large constituencies that might vocally oppose the moves. By contrast, there was an outpouring of concern among disability advocates amid rumors that special-education programs would be moved.

The senior department official said Tuesday that the interagency agreements will ensure that experts from the Education Department still manage the day-to-day operations of the programs.

Federal law requires that many of the programs be housed in the Education Department. The interagency agreements amount to a work-around under which policy decisions will remain with the Education Department but the programs will be administered elsewhere. Staffers who work on the programs are expected to move to the new agencies.

The senior official said these types of arrangements have been used many times before. But in this case, officials are hoping that the transfers will lay the groundwork for eventually closing the agency altogether.

The announcement was welcomed by House Education Committee Chairman Tim Walberg (R-Michigan), who has noted that there is not enough support in the Senate to pass legislation to eliminate the department.

On Tuesday, he praised the actions as a much-needed break from the status quo at the Education Department, where, he contended, bureaucracy and liberal ideology have wasted taxpayer dollars and failed students.

“The Trump administration is making good on its promise to fix the nation’s broken system by right-sizing the Department of Education to improve student outcomes,” he said. “It’s time to get our nation’s students back on track.”

But public education advocates were furious.

“This administration is taking every chance it can to hack away at the very protections and services our students need,” Becky Pringle, president of the National Education Association, said in a statement.

McMahon has made the case for eliminating the Education Department in appearances across the country. Last month, department spokeswoman Madi Biedermann said the agency was exploring the move of special-education services to another agency.

“Secretary McMahon has been very clear that her goal is to put herself out of a job by shutting down the Department of Education and returning education to the states,” Biedermann said in October.

The Trump administration laid the groundwork for this change earlier this year when it signed an agreement to move career, technical and adult education grants out of the Education Department to the Labor Department. Under the arrangement, Education retains oversight and leadership while managing the programs alongside Labor, a way of sidestepping the federal statute.

“We believe that other department functions would benefit from similar collaborations,” McMahon wrote in an op-ed essay published Sunday in USA Today.

More broadly, McMahon argued that the recently ended government shutdown showed how unnecessary her agency is.

“Students kept going to class. Teachers continued to get paid. There were no disruptions in sports seasons or bus routes,” she wrote. “The shutdown proved an argument that conservatives have been making for 45 years: The U.S. Department of Education is mostly a pass-through for funds that are best managed by the states.”

The agency has taken other steps to shrink itself, including reducing its staff, which stood at 4,133 at the start of Trump’s term. That number was cut by about half earlier this year through layoffs and incentives to resign or retire.

The administration also tried to lay off an additional 465 people during the shutdown, a move that was blocked by a court and then reversed in the legislation signed to reopen the government.

After the government reopened, the Education Department mocked itself as irrelevant.

On social media, it posted a fake out-of-office message that it jokingly suggested its workers use: “We might be away from our desks … creating more red tape, and doing nothing to improve student outcomes.” It was signed, “Bureaucratically Yours.” In another post, the agency asked, “Let’s be honest: did you really miss us at all?”

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0