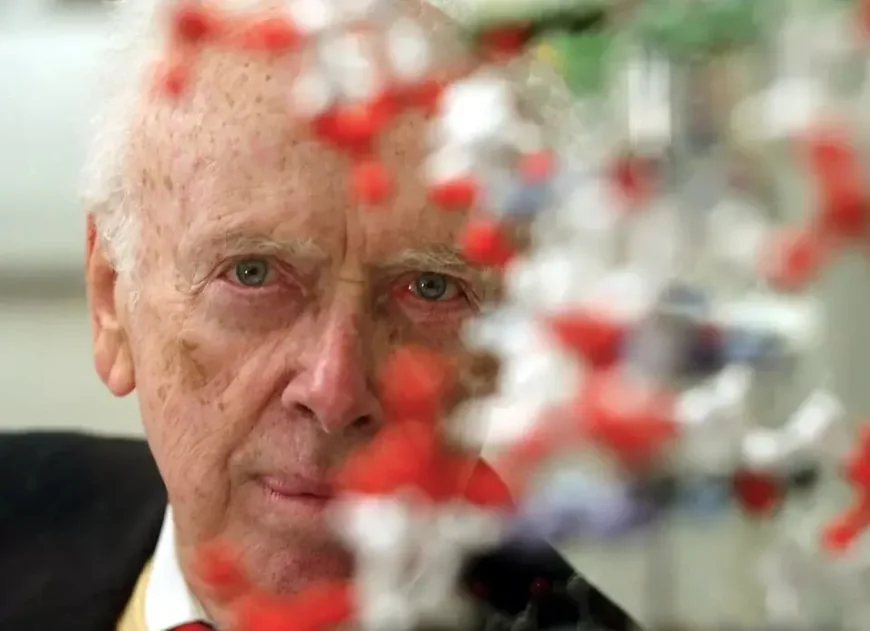

James Watson co-discoverer of DNA's double-helix structure has died

James D. Watson, whose 1953 co-discovery of DNA's twisted ladder-like structure revolutionized the fields of medicine, crime prevention, genealogy, and ethics, has died at the age of 97.

This remarkable achievement, achieved by Chicago-born Watson at just 24 years old, made him a respected figure in the scientific world for decades. But toward the end of his life, he faced condemnation and professional criticism for offensive comments, including suggesting that Black people are less intelligent than White people.

Watson shared the 1962 Nobel Prize with Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins for discovering that deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, is a double helix, consisting of two strands that coil around each other to form a long, gradually twisting ladder-like structure.

This discovery was a major breakthrough. It immediately clarified how genetic information is stored and how cells copy their DNA when they divide. This replication begins with the separation of the two strands of DNA like a zipper.

Even among non-scientists, the double helix became an easily recognizable symbol of science, appearing in places like Salvador Dali's works and a British postage stamp.

This discovery opened the door to modern advances such as altering the genetic structure of organisms, treating diseases by inserting genes into patients, identifying human remains and criminal suspects from DNA samples, and tracing family trees and ancient human ancestors. But it also raised many ethical questions, such as whether we should alter the body's blueprint solely for cosmetic reasons or in a way that would also be passed on to a person's offspring.

Watson once said, "Francis Crick and I had made the greatest discovery of the century; it was absolutely clear." He later wrote: "We could not have imagined the explosive impact of the double helix on science and society."

Watson's laboratory never made such a major discovery. But in the decades that followed, he wrote influential textbooks and a bestselling memoir and helped guide the project to map the human genome. He selected and supported talented young scientists. And he used his reputation and contacts to influence science policy.

Watson died in hospice care after a brief illness, his son said on Friday. His former research laboratory had confirmed his death a day earlier.

Duncan Watson said of his father, "He never stopped fighting for people suffering from diseases."

Watson's initial motivation for supporting the gene project was personal: his son, Rufus, was hospitalized with a possible diagnosis of schizophrenia, and Watson thought that knowing the complete structure of DNA would be crucial to understanding that disease—perhaps helping his son in time.

In 2007, he received unwanted attention when London's Sunday Times magazine quoted him as saying he was "inherently pessimistic about Africa's prospects" because "all our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours—even though all the tests don't actually say that." He said that although he hoped everyone would be equal, "those who have to deal with Black employees don't find that to be true." He apologized, but after massive international outcry, he was suspended as Chancellor of the prestigious Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York. He retired a week later. He had served there in various leadership positions for nearly 40 years.

In a television documentary aired in early 2019, Watson was asked if his views had changed. He said, "No, not at all." In response, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory revoked several honorary degrees awarded to Watson, stating that his statements were "reprehensible" and "not supported by science."

The combination of Watson's scientific achievements and controversial remarks created a complex legacy.

Dr. Francis Collins, then director of the National Institutes of Health, said in 2019, "He displayed a regrettable tendency to make inflammatory and offensive remarks, especially toward the end of his career." "His outbursts, especially when they focused on race, were deeply misleading and deeply hurtful. I wish Jim's views on society and humanity had matched his brilliant scientific insights."

Long before this, Watson detested political correctness.

In his 1968 bestselling book, "The Double Helix," about the discovery of DNA, he wrote, "A considerable number of scientists are not only narrow-minded and dim-witted, but also stupid."

To succeed in science, he wrote: "You must avoid stupid people. ... Don't do anything that bores you. ... If you can't keep pace with your true peers (including scientific competitors), get out of science. ... To achieve a great success, a scientist has to be in deep trouble."

It was in the fall of 1951 that the tall, skinny Watson — already the holder of a Ph.D. at 23 — arrived at Britain’s Cambridge University, where he met Crick. As a Watson biographer later said, “It was intellectual love at first sight.”

A reporter asked him 2018 if any building at the Cold Spring Harbor lab was named after him. No, Watson replied, “I don’t need a building named after me. I have the double helix.”

His 2007 remarks on race were not the first time Watson struck a nerve with his comments. In a speech in 2000, he suggested that sex drive is related to skin color. And earlier he told a newspaper that if a gene governing sexuality were found and could be detected in the womb, a woman who didn’t want to have a gay child should be allowed to have an abortion.

More than a half-century after winning the Nobel, Watson put the gold medal up for auction in 2014. The winning bid, $4.7 million, set a record for a Nobel. The medal was eventually returned to Watson.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0